Selective representation

By Christian Block, Misch Pautsch, Lex Kleren Switch to German for original article

Listen to this article

Within three decades, the number of nationalities represented on the country's territory has doubled. Do the media reflect the country's growing diversity? Three perspectives.

This article is provided to you free of charge. If you want to support our team and promote quality journalism, subscribe now.

Ehsan Tarinia's realm is a small office overlooking Echternach's market square. Far from the leading media, almost all of which are based in the capital, the political centre of the country, Tarinia, who came to Luxembourg from Iran in 2005 and applied for asylum here, writes news for the news platform he founded, Simourq News.

The idea of a news portal came to him in the context of the corona pandemic. In this exceptional situation, it was important for the entire population to have quick and comprehensive information about what was happening and the measures in place. "I shared all health-related news, " Tarinia recalls. At first, he did this only in Persian. Then he expanded the portal, first to other topics, later to other languages such as English, Arabic and Kurdish. With its contributions, Simourq News addresses immigrants who do not yet speak any of the official languages; a process that takes time. "There are often barriers to accessing information during the initial stages of settlement. We aim to bridge this gap by providing content in multiple languages to ensure that all residents, regardless of their language proficiency, can stay informed about important matters."

For example, the portal reported on the Cargolux strike, the shortage of doctors or election campaign events. But general information about the country is also included. In the past, Ehsan Tarinia repeatedly found that despite introductory courses, many immigrants "know nothing about the politics, history or geography of Luxembourg". The focus on refugees and immigrants also means taking up topics that are of particular interest to them and that may be neglected in other media. As an example, he mentions a contribution about political parties in Luxembourg, also to explain what a political party is and to draw a comparison with the political system in Iran. In his circle of acquaintances, there were people who thought the LSAP was a trade union, Tarinia tells us during the on-site interview.

"There are often barriers to accessing information during the initial stages of settlement."

Ehsan Tarinia, Simourq News

Simourq News is one of the media formats probably little known to the general public, many of which have emerged as a result of the pandemic, targeting specific communities in the country. In fact, Luxembourg's demographic development in recent years has been twofold. On the one hand, it is well known that the population is growing, by more than 100,000 inhabitants in the last decade. On the other hand, and this is perhaps less well known, the Grand Duchy has become increasingly international in recent decades: the number of nationalities represented on the territory has doubled to 180 within 30 years. Do the established media do justice to this diversity, in linguistic, cultural and social terms?

Pascale Zaourou and Sérgio Ferreira agree that representing all nationalities would be a difficult matter. "The [social] diversity is definitely present, although occasionally in a rather exaggerated way, " says the Asti political director, for example. Ferreira notices for instance that the Portuguese community in Luxembourg is mostly reported on when the Portuguese president is visiting, there is a football match or the annual Fatima pilgrimage to Wiltz is coming up. However, he also believes that "what sometimes goes on within communities or in certain issues concerning the presence of foreigners […] is treated almost casually." And often only selectively, for example when an institution or non-profit organisation once again puts its finger in the wound with a study or communication. What he missed in the broad national reporting was, for example, the monitoring report on Luxembourg published in mid-September by the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), an organ of the Council of Europe. Or that in the context of the polemic about begging in the municipal elections, people living on the street were only spoken to in a rather superficial way, if at all.

Pascale Zaourou on positive representation

*in french

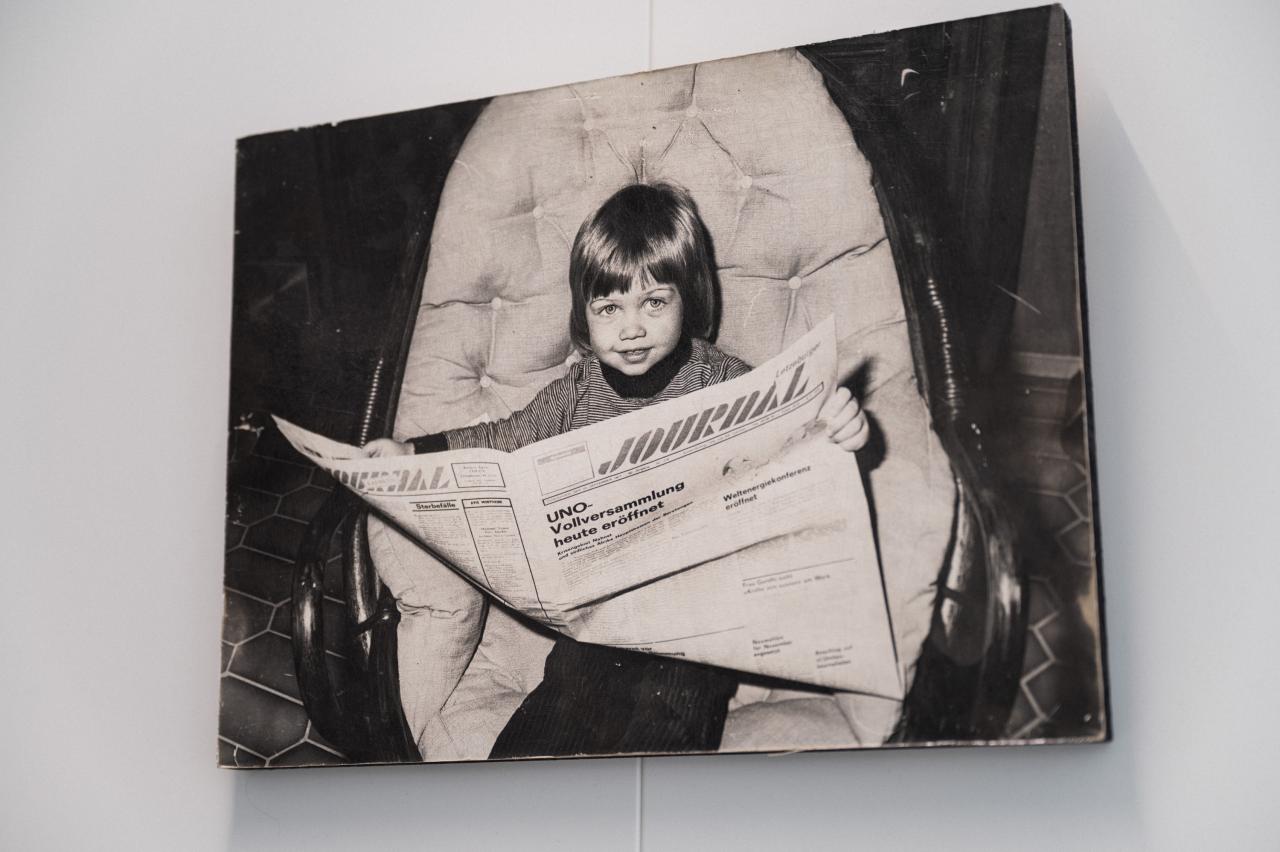

Ehsan Tarinia

Sérgio Ferreira does not want to badmouth everything. On the one hand, he is aware of the pressure that journalists are under, where there is often little time for in-depth research, or of the difficulties, which were even more pronounced in the past, in accessing sources who are willing to entrust themselves to a journalist. On the other hand, there are of course examples of high-quality journalistic work on topics such as the working poor or the right to housing. And he welcomes the fact that the public debate on racism and discrimination has been gaining weight in recent years. Even if he notes, "It's a bit bizarre that in 21st century Luxembourg, with the demographics the country has, we're only at the beginning of factually and scientifically coming to terms with these phenomena."

For her part, Pascale Zaourou, president of the umbrella organisation of associations from immigration (Clae) since 2021, speaks of a "comparatively selective representativeness" via the choice of languages in which media report. By choosing one or more languages, the media would address a certain audience, but at the same time exclude another. She finds more diversity in radio broadcasts. By this, she seems to be referring to Radio Ara, which, according to the station, now broadcasts in ten to twelve languages in its community programmes, including Arabic, Polish, Greek, Russian, Ukrainian or Spanish (for a South American audience). The volunteers behind these formats cater to the needs of their community or provide them with the information they need to live in Luxembourg, the station adds.

Illusion of diversity?

At first glance, there seems to be no shortage of English-language media reporting on life in Luxembourg today. Just as there is a range of French or Portuguese information sources. But do these media also represent the interests of all those who share the respective language of communication? Or do English-language media perhaps cater too much to better-off expats for whom Luxembourg is a detour on their CVs, as well as their employers who can act as potential subscribers and advertisers? Does linguistic diversity perhaps create an illusion of diversity, at least to some extent?

"In the last ten years in particular, English has emerged as a language by means of which one can communicate with most people in Luxembourg, in addition to the official languages."

Sérgio Ferreira, Political Director of Asti

For Sérgio Ferreira, this could be food for thought for the English-language media. Because for many fellow citizens from Africa or Latin America, "English could be a language of integration, or at least a language of first contact with Luxembourg society". Pascale Zaourou is thinking along similar lines. The interest of the 200 or so member associations represented by the Clae Committee in the settlement of any corporations or in highly technical financial topics is limited, she says. There is a need for practical information and access to reporting on the issues that shape society, she says.

Ehsan Tarinia is of the opinion that the various publishing houses – he speaks of a "media war" – instead of giving themselves a principle and staying true to it, "want to cover everything" like some sort of supermarket. Moreover, they were mainly after followers.

Another phenomenon can contribute to the fact that parts of society do not find themselves in the media. Uwe Krüger, a researcher in the Department of Journalism at the Institute for Communication and Media Studies at the University of Leipzig, called it a "media mainstream" in a 2016 article for the journal Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte: "the phenomenon that at one point in time the majority of the leading media cover a certain topic or hold a certain opinion".

Pascale Zaourou on opening up the editorial offices

*in french

Pascale Zaourou

A statement that can certainly also be applied to Luxembourg and which Krüger elaborates as follows: "Since the attention structures in different newsrooms are similar and many journalists ascribe similar characteristics to the same events, news selection can also be similar. Journalists also observe each other. One receives other media in order to come up with ideas for topics, to compare one's own position and to ensure the competitiveness and connectivity of one's own reporting with the audience."

Journalists as a reflection of society?

But the biographical profile of journalists – educational level, socio-economic background – can also be a factor. The Media Pluralism Monitor, for example, showed that in Luxembourg, only a few women act as co-editors in the mainstream news media.

Furthermore, it can be assumed that the editorial offices show a rather homogeneous profile of journalists, in which people from third countries, for example, are likely to be underrepresented. This does not mean per se that journalists do not enjoy freedom in their choice of topics and their approach, which is part of the appeal of the profession. But don't different perspectives, such as the perspective of third-country nationals, risk being underrepresented? And that this view is also carried over into multilingual reporting, which is supposedly aimed at a more international audience, where contributions from a "core editorial team" are translated into French, English, Portuguese or other languages? This is a phenomenon that Ehsan Tarinia claims to observe quite frequently, at least. It would certainly be worth a closer look.

"If a medium is English-speaking but addresses everything that is economics in an almost technical way, it already excludes a lot of people."

Pascale Zaourou, Clae president

In any case, Ferreira shares the assessment that the "white European male", to put it somewhat exaggeratedly, is "in fact quite present" in the editorial offices. The former journalist points out that "diversity within the editorial offices also depends on the medium and its audience. […] In the more Luxembourgish media (audiovisual, ed.), diversity is less pronounced than in other media, which are more diverse from the outset simply by virtue of being multilingual." Which in turn is also expressed in the selection of guests invited to the studios of the audiovisual media, first and foremost the Luxembourgish-speaking ones. Even if some things have changed, the recent Polindex study, taking into account the methodological concerns pointed out by Fernand Fehlen in an article in the monthly forum, has shown that the dominant place of Luxembourgish in the political sphere today means the exclusion of many foreign citizens. This makes not only the journalists in the political bubble but also the political parties responsible.

The recent Media Pluralism Monitor rated social inclusion at a critical medium level, focusing mainly on the media with a public mandate. Despite improvements in recent years, the report questioned "to what extent we [can] talk about an efficient public service media if the media does not

reach a substantial part of the population due to language limitation". Interestingly, the report also concluded that the private radio and print sector was "more proportional" in terms of representation of "linguistic minorities" (Portuguese, Italian, French, German…).

Pascale Zaourou adds: "It would be interesting to facilitate access to information professions, that editorial offices are open to immigrant journalists." She points to the media's great responsibility to inform the widest possible audience. Which also means being aware that the population cannot simply be divided into "Luxembourgers" and "non-Luxembourgers". Or that citizenship goes beyond mastering the national language, or "unfortunately" is not always synonymous with being confident in the use of the Luxembourgish language. Nevertheless, this reality had to be taken into account in the media and in the coverage of, for example, political issues. The election campaign, on the other hand, had been conducted largely in Luxembourgish.

Pascale Zaourou on the example of the drug problem in the station district

*in french

Sérgio Ferreira

For Pascale Zaourou, it would therefore be important to extend the subtitling of national and local television programmes in the official languages, as well as to English as a kind of universal language. Given the composition of the population, Portuguese could also be taken into account in order to reach the largest possible audience on the one hand and to promote the understanding of the Luxembourgish language for all on the other. She advocates seeing translation as a tool to share Luxembourgish cultural heritage with the whole population. Translation thus contributes to the collective memory – and should in no way be interpreted as an attempt to diminish the status of Luxembourgish.

What the Clae president misses overall in the media is, for example, the cultural aspect. To put it bluntly, she means that it is not enough to talk only about neighbourhood festivals and gastronomic specialities, but also to show an openness towards the intellectual culture of the respective community, to show interest in its writers, painters, in other words, its culture or history. She mentions, for example, the commemorations in Luxembourg of the 49th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal. "I'm not sure if it was talked about much in the media."

Or, in terms of balanced reporting, letting both sides have their say on an issue. This leads us to talking about the situation in front of the central station and the heated atmosphere in this district of the capital, whose residents recently made a statement at a demonstration.

"It is clear that, especially in the audiovisual media, [social] diversity is not present, neither at the editorial level, nor in terms of the topics covered."

Sérgio Ferreira

"[People] don't stop saying that there are too many dealers [around the station] and you talk about Nigerians. Have they spoken to a single Nigerian? I doubt it, " Zaourou elaborates, before adding: "La répétition devient leçon." Which can be understood as follows: If you always put people of a certain origin in a negative context, it rubs off on the whole community, if not on people of a certain skin colour or foreigners as a whole. Positive aspects would be lost in this portrayal. She refers, for example, to a non-profit association of Nigerians in Luxembourg that supports single parents in their country of origin. Or the examples of fellow citizens with foreign roots who contribute in their own way to the common good of Luxembourg.

All interviewees agree that more recognition could be given to newspapers and radios organised by citizens and associations. "With a little more support, this voluntary activity could possibly develop into something more permanent, " says Pascale Zaourou – even though she is actually more concerned that the professional media should take more account of diversity.

Ehsan Tarinia and his team would certainly appreciate financial help. So far, he has not received any official support.