Party newspapers no more

By Camille Frati, Misch Pautsch, Lex Kleren Switch to French for original article

Listen to this article

Once so close together in the 20th century, Luxembourg's newspapers and political parties have gradually drifted apart to achieve a claimed distinction today – even if the past still clings to them.

This article is provided to you free of charge. If you want to support our team and promote quality journalism, subscribe now.

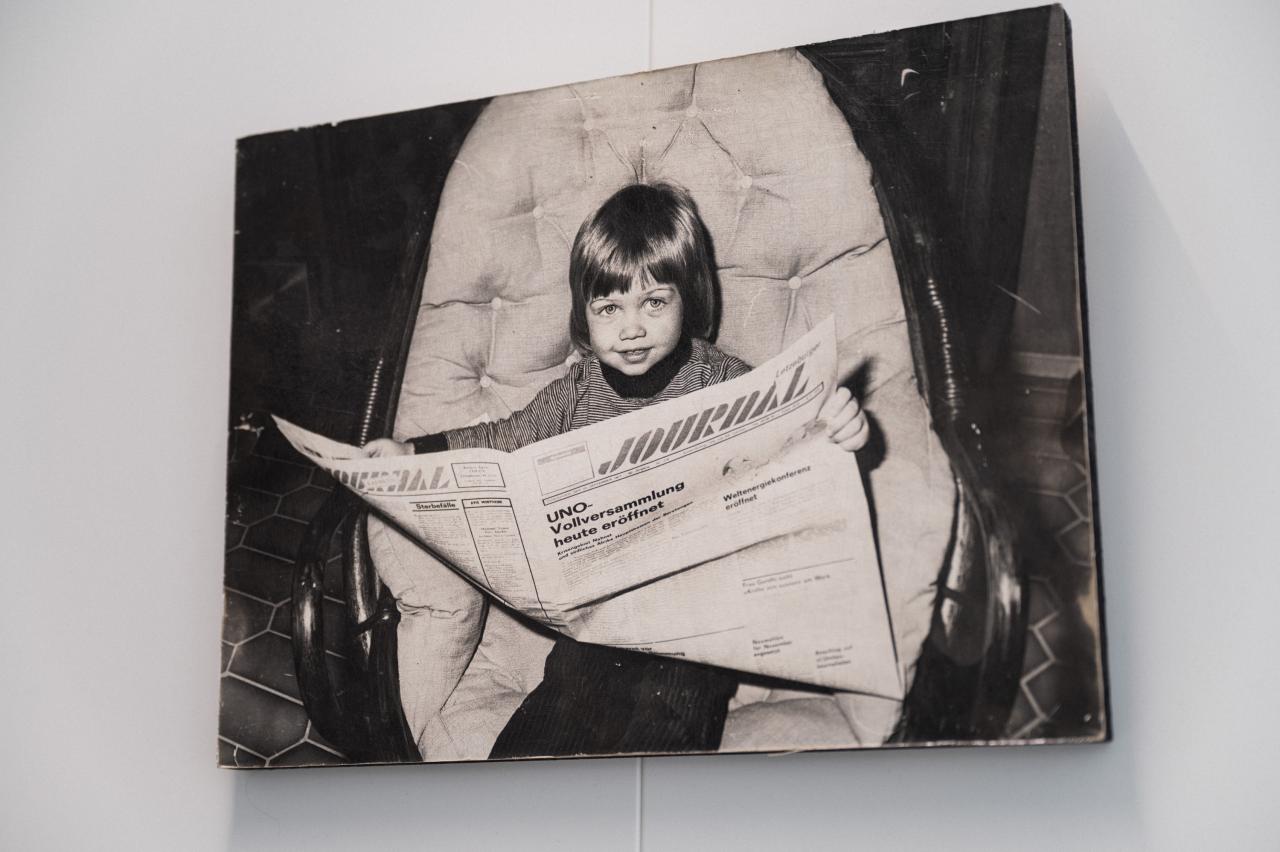

Looking at the front pages of the Grand Duchy's leading daily newspapers the day after the parliamentary elections, it would be difficult to pinpoint the political inclinations of any one party. "Luxembourg voted for change" soberly headlined the Luxemburger Wort, while the Tageblatt wrote "Gambia is ancient history" (Gambia ist Geschichte). There's nothing to suggest that the former has historical links with the CSV and the latter with the LSAP. And yet these roots exist and have endured until recently. In addition to the two titles mentioned, the Lëtzebuerger Journal was associated with the DP, Grénge Spoun (now Woxx) with déi gréng and the Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek with the KPL communist party – the only one that still assumes and claims this kinship, since it is still edited and directed by Ali Ruckert, president of the KPL.

"The Party of the Right, the Church and the Wort: this is the triumvirate that has dominated political life since universal suffrage."

Romain Hilgert, former editor-in-chief of Lëtzebuerger Land

In reality, it's not the parties that have created newspapers under their control, but almost the opposite. "The Wort is 175 years old this year: it was founded in 1848 when censorship was abolished in the Grand Duchy, " recalls Roland Arens, a long-standing journalist at the Wort and its editor-in-chief since 2017. "In Luxembourg – and not only in Luxembourg – most newspapers predated the parties, " points out Romain Hilgert, former editor-in-chief of Lëtzebuerger Land and author in 2004 of the reference work on the Grand Ducal press: Les journaux au Luxembourg 1704–2004, commissioned by the government's information and press service (SIP). "The Wort is older than the Party of the Right (predecessor of the CSV, editor's note), just as the Tageblatt (born in 1913) stems from the social-democratic and trade-union movement that preceded the LSAP. And this is especially true for the liberals: the liberal press was hegemonic throughout the 19th century through the Courrier du Grand-Duché and then the Luxemburger Zeitung, which remained the largest newspaper until the First World War. But before that war, the liberal party didn't exist as such, it was several factions that killed each other and merged again."

At the end of the Second World War, the political landscape shifted. "The government that went into exile in Portugal and then in Canada was very unpopular when it came back; the population had the impression that it had been living the good life while under Nazi occupation, " Hilgert recounts. "It was a tour de force to regain power for the governing parties." Particularly for the Social Democratic Party (LSAP's predecessor), which had gone abroad while the Communist Party dominated the big factories. The Party of the Right, in fact, could count on two heavyweight supporters: the Church and the Wort. "It was the triumvirate that had dominated political life in the Grand Duchy since universal suffrage (acquired in 1919). The Church also had an army of secular associations: scouts, Christian-social women, craftsmen… The landscape was largely locked in by the right in the center and north of the country, while in the south left-wing parties dominated." A division that corresponded exactly to that of newspaper readership: the lands of the CSV were acquired by the Wort, the others by the Tageblatt and the Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek. The Lëtzebuerger Journal, born of the merger of Obermoselzeitung and D'Unio'n in 1948, accompanied the reformation of the liberal political movement under the name Groupement démocratique.

Romain Hilgert

Coalitions come to power one after the other – the CSV invariably the strongest party, with the Groupement Démocratique and LSAP taking turns as junior partners. Each newspaper supports the party of which it is the official organ. "In the 1960s, the Journal 's editor-in-chief was also a Liberal MP and a member of the bureau of the Chamber of Deputies, " recalls CSV MP Marc Spautz, whose father Jean Spautz sat in the Chamber at the time. "And before the Second World War, the vicar-general was vice-president of the CSV parliamentary group and editor-in-chief of the Wort. Later, Jacques Poos was a member of parliament and editor-in-chief of the Tageblatt." Close ties therefore existed between the newspapers and their parent parties.

"Until the late 1960s, newspapers were fairly opportunistic and supported coalitions, " notes Hilgert. "But in May 1968, the trade unions no longer wanted the eternal conservative coalitions supported by the Socialist Party. So the Tageblatt dissociated itself somewhat from the Socialist Party, which also underwent a split between the Social Workers' Party and the Social Democratic Party. The Tageblatt became a more left-wing newspaper, it was against the Vietnam War, for the student movement and above all it supported the unions, i.e. its owner (the LAV Central, predecessor of the OGBL, editor's note), for a social offensive to modernize the conservative society dominated by the CSV."

A fading divide

The 1960s and 1970s were still characterized by sharp differences between the parties. "Back then it was more important to be a good campaigner than a good journalist, and there were relatively few journalists trained in foreign schools, " adds Hilgert. "The last great ideological war was the coalition between the Liberals and the Socialists between 1974 and 1979. The Wort and the CSV were taking potshots at the Tageblatt and the government." It was indeed the first coalition without the CSV since the Second World War – and a coalition that gave a boost to societal reforms so difficult or impossible to achieve with the Christian Socialists, such as the abolition of the death penalty, the right to abortion or no-fault divorce. "Then the steel crisis forced a national agreement to save the steel industry and the national economy, " says Hilgert. "There were no longer any parties, just Luxembourgers paying taxes to save the steel industry."

But while political and ideological cleavages were attenuated, newspapers and parties remained close. "In the 1980s, the links between parties and newspapers were still very close, " says Armand Back, editor-in-chief of Tageblatt. "There was a Tageblatt journalist sitting at the table in LSAP committees, and it was the same for the Wort and CSV." In 1976, none other than Tageblatt editor Jacques Poos (MP since 1970) joined the government as Finance Minister, before returning as Deputy Prime Minister in 1984 alongside Jacques Santer.

"We are of course a newspaper close to the OGBL's union and actions, not because they emanate from the OGBL but because our ideas are the same."

Armand Back, editor-in-chief of Tageblatt

For Mr. Hilgert, the Wort was actually more attached to its shareholder, the archdiocese, than to the CSV. "The Wort has always been almost more right-wing than the CSV. It was the newspaper of the clergy, of a more conservative Church. It is often forgotten that the Wort defended very conservative and reactionary positions in its foreign pages: it supported apartheid in South Africa, the Pinochet putsch in Chile and also the Vietnam War. It had very reactionary correspondents all over the world. It was the time of [André] Heiderscheid (priest and managing director of the Saint-Paul group, editor's note) and [Léon] Zeches (editor-in-chief, editor's note), who were very, very, very right-wing."

1988 saw the birth of the latest offspring in the family of party-linked newspapers: Grénge Spoun. "Grénge Spoun's name is a play on words, referring to both verdigris and inexperienced environmentalists, " comments the book Les journaux au Luxembourg. Several deputies from Déi Gréng – which entered the Chamber of Deputies in 1984 – wrote for the monthly magazine dedicated to environmental protection and alternative culture. In 2000, however, the magazine cut its ties with the party and, eager to open up to a wider readership, changed its name to Woxx. On its website, the magazine claims to be "a press organization independent of political parties and the economy".

Roland Arens

This was also the period when Luxembourg's historically party-oriented newspapers began to fall by the wayside. The Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek obviously took a beating with the demise of the USSR, as did the KPL, which bid farewell to the Chamber of Deputies in 1994. The Wort, on the other hand, enjoyed a successful decade. "In its heyday, the Wort was the episcopate's cash cow, " says Hilgert. "It held a virtual monopoly on press advertising, while the market shares of the Tageblatt and the Journal remained marginal. It published business advertisements, obituaries, classifieds, etc. It achieved historic circulation figures in the 1990s before seeing them plummet. It then experienced very serious financial problems and launched several redundancy plans to lay off journalists and printing workers."

At the same time, the 2000s saw the first serious rift between the Wort and the CSV. "When the CSV rejuvenated itself through [Jean-Claude] Juncker, the Wort became more or less critical of the government, the party and Juncker, " Hilgert continues. "He uttered the famous line: 'My office is in the shadow of the cathedral and I'm interrupted every time its bells ring'. This was very badly received by the clergy. At the time, Mr Juncker was young and provocatively modern. He always played with the image that he wasn't a Paf (priestling, ed.). But as the Church had lost many members, it needed the CSV's support in government to defend Catholic education in schools and the fact that the state paid priests."

The Wort shareholder was therefore also appalled to see the vote on the euthanasia law, which originated from an LSAP-déi gréng bill but was taken up by the Juncker-Asselborn I government. "Juncker allowed this vote because he freed the CSV deputies from voting instructions. And they voted for it, " recalls Hilgert. "The Wort was against it, just as it was against the openings wanted by the CSV on abortion and divorce."

From economic problems to political emancipation

At the same time as the Wort began to distance itself from the CSV – or vice versa – the Luxembourg media, like their counterparts in neighboring countries, were confronted with far-reaching economic change. The democratization of the Internet has diverted part of the advertising revenue previously earned by newspapers, whether from advertisers or individuals. At the same time, newspapers have shot themselves in the foot by giving free access to all articles on their websites. "It's an education that newspapers have missed out on, " laments Hilgert. "At the time everyone was discovering the internet, they put everything online for free and then it was too late to put up a [pay] wall."

No newspaper in the Grand Duchy has been spared economic hardship, whether behemoths like the Wort and the Tageblatt, flagships of diversified groups, or more modest players like the Lëtzebuerger Journal – which had never really enjoyed a prosperous period economically speaking, almost disappearing in 1964, strangled by the Imprimerie Centrale's tariffs. After the expansion phase came the downturn: in 2011, Wort stopped publishing La Voix du Luxembourg, its French-language paper edition, and then Point24, its free daily that was supposed to compete with L'Essentiel. Editpress reacted later by closing Le Jeudi in 2019, its weekly newspaper whose print run has always been inflated in relation to actual readership – 15,532 copies printed for 1,618 issues bought in 2017 according to the Media Information Center (CIM, Belgium).

This comes as a shock, since two of these publications benefited from press subsidies, a guarantee of pluralism that the DP-LSAP government introduced in 1976 to support newspapers in the face of the all-powerful Wort – which is still the main beneficiary today. "Aid to the Luxembourg press is high in Luxembourg – it's equivalent to that of the Austrian or Belgian states, in a much smaller market", explains Christian Lamour, researcher at Liser and author of several publications on the Luxembourg press. "If you don't help the press, it disappears, and that's not good for democracy."

These economic difficulties largely explain the accelerated political mutation of Luxembourg newspapers. "The logic of distancing the media from political parties is linked to a major trend in journalism, which means that as readership declines, newspapers are positioning themselves as an information press rather than an opinion press, in order to attract the widest possible readership, " says Lamour. "In many subjects, you can't distinguish the political color associated with the newspaper." The Media Pluralism Monitor 2022 points to another underlying trend: "As the journalism profession requires more and more versatility, journalists specializing in politics have become rare and go out into the field much less, which has the effect of limiting encounters between politicians and journalists."

"Luxembourg press support is strong in Luxembourg – its mass is equivalent to that of the Austrian or Belgian states, in a much smaller market."

Christian Lamour, Liser researcher

So in 2012, faced with a collapse in its figures, the Lëtzebuerger Journal underwent a "relaunch" in the hands of its editor-in-chief since 2005 Claude Karger. "We carried out a series of market analyses and came to the conclusion that we had to get away from the idea that the Lëtzebuerger Journal was the official organ of the DP – enshrined as such in the party statutes. We wanted to open up to new sections of the readership, and other considerations also came into play, such as languages and internet presence." But with no substantial resources invested, the deadline was only postponed until 2020, when the daily plummeted, weighed down by the drop in advertising in the context of Covid-19. The Journal was reborn in early 2021 exclusively on the internet. Officially removed from the PD's articles of association, it has a new, independent editorial line.

Even the Church has come to terms with the Wort's editorial line. "The Church said to itself: this is dramatic for us as believers, but we have to unleash the Wort to remain competitive, " explains Hilgert. So, from 2013, Marc Glesener and Jean-Lou Siweck tried the route of a modern conservative newspaper. "They failed after a few years. It was Luc Frieden (who became chairman of the board in 2016, ed. note) who pulled the brake." Siweck left the Wort in autumn 2017 due to "differences over the editorial line". Employees report internally that the former CSV finance minister blames Siweck for "a swing to the left" and for "distancing himself from the CSV". This version is refuted by Roland Arens, who was appointed editor-in-chief following Jean-Lou Siweck's departure: "It's an oft-repeated impression that I can't confirm. But I must point out that the editorial line of the Wort written under his impetus has not changed to this day."

Christian Lamour

Arens calls for "diversity within the editorial team and, above all, diversity of opinion, with the opinion pages open to contributions that are not at all in line with the newspaper's editorial line, or even with a certain political line", with a view to "informing the reader". In any case, CSV has taken note of Wort's change of direction. "When I analyzed the 2018 parliamentary elections, I wrote that we no longer had the support of the Wort as in previous elections, " remarks Marc Spautz. "Whereas with the Socialists, the Tageblatt was really objective but had again taken a small turn six weeks before the elections, which is understandable – the LSAP is one of the shareholders." So in February 2023, when the CSV announced that it had chosen Luc Frieden to carry its colors in the legislative elections, journalist Michèle Gantenbein painted an uncompromising portrait in the Wort under the not unironic title "Der Heilsbringer der CSV" (The Savior of the CSV).

In fact, the Church cut its material ties with the Saint-Paul group by selling it to Flemish publisher Mediahuis in 2020, after relinquishing the board of directors to a layman – Luc Frieden – in 2016. The "cash cow" is now a thing of the past, even if the Mediahuis press release is careful to specify that "the media" [of Saint-Paul] will continue to cover religious topics and Church communication with all the necessary professionalism".

Similar ideas

While Tageblatt still counts the LSAP among its shareholders – 2.12% according to Paperjam (October 2020 issue) – it has long since ceased to see itself as the party's newspaper, or indeed as the newspaper of the OGBL trade union. "The LSAP was the first party to realize that it no longer had a newspaper, " notes Spautz. The economic and financial crisis of 2008, which really hit Luxembourg three years later, had passed through. The austerity budget concocted by Luc Frieden, Finance Minister in the Juncker-Asselborn II government, was heckled by the CSV and LSAP parliamentary fractions, but the changes made did not appease the Tageblatt's critics. Just like the bipartite talks organized in 2014 under the Gambia coalition instead of a tripartite, with the social partners unable to find any common ground to tackle the crisis in the Grand Duchy.

"LSAP is a very minority shareholder and is not even involved [in the life of Tageblatt], " assures Armand Back. "Since I took office last November, I have never been contacted by LSAP politicians to tell me to write this or that. And if they did, we'd tell them it doesn't work like that. It used to work differently in the 1980s, but that kind of relationship disappeared a long time ago."

Audiovisual

-

It's a historical incongruity that continues to raise questions in the 21st century: why are three seats on the Board of Directors of CLT-UFA, the parent company of RTL Luxembourg, occupied by politicians? At the time of writing, the three lucky directors were Gilles Baum (DP), Yves Cruchten (LSAP) and Claude Wiseler (CSV). The outcome of the recent parliamentary elections may well lead to a game of musical chairs, as Cruchten was not re-elected to parliament, while Wiseler, re-elected, may well take up a ministry in the next government. Although not re-elected, Baum should benefit from the appointment to the government of one of the MPs from his constituency (East).

"It's not unusual in other countries for political parties to be represented on the board," stresses Oliver Fahlbusch, spokesman for RTL Group. "They are there as members of civil society, and this is in keeping with RTL Luxembourg's public service mission." Details of this can be found in the highly secretive concession agreement between the state and RTL Group.

In any case, RTL Luxembourg wishes to make clear what its editorial line affirms: "We do not exert any external influence on news reporting, nor do we succumb to any external political or economic influence. (...) Management in particular does not interfere with editorial decision-making or restrict the independence of our editorial staff."

Tageblatt insists on keeping its distance from the LSAP – whether or not it comes to power in the new parliamentary term. "We will be vigilant with regard to the government and what it is going to do, but also with regard to what the LSAP is going to do as an opposition party." Politics aside, the newspaper from Esch-sur-Alzette – now based in Belval – claims to be above all "a humanist newspaper, positioned on the left of society". It also claims to be "truly independent of the OGBL" – ruled by Nora Back, Armand's sister. "That wasn't the case a few years ago, since the Siweck era (who chaired the board of directors between 2017 and 2021) it's changed a lot and we've stayed with that change. We are, of course, a newspaper close to the OGBL's union and actions, not because they emanate from the OGBL but because our ideas are the same. It's a question of the paper's identity, a necessary identity because being colorless, odorless and insipid would lead to nothing."

"We don't have to prove that we are not the mouthpiece of the CSV."

Roland Arens, Editor-in-Chief of Luxemburger Wort

As a result, three of Luxembourg's four former party newspapers (Luxemburger Wort, Tageblatt, Lëtzebuerger Journal and Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek) have now broken ranks. However, this past seems to be sticking to them. "We don't have to prove that we are not the mouthpiece of the CSV", insists Arens, defending the Wort editorial team. "It's a very biased view looking to the past, which I can understand, but which doesn't correspond to any reality." Ditto for Armand Back: "In the editorial department, we don't ask ourselves the question 'what will the LSAP or the OGBL say?'"

Ironically, it's this historical link that may save them in the long run. For although parties and newspapers are no longer linked, they share similar ideas, and this relay in public opinion remains invaluable for political parties. That's why the Bettel government has reformed press subsidies in 2021, having already extended them to online news sites. "Abandoning a daily newspaper means a loss of political prestige", Hilgert points out. It remains to be seen whether the new press subsidy scheme, which is more generous for most titles – with the exception of Le Quotidien – will stabilise pluralism of opinion, a key element of a healthy democracy.