75 years in the life of Lëtzebuerger Journal

By Camille Frati, Lex Kleren, Misch Pautsch Switch to French for original article

Listen to this article

The longevity of the Lëtzebuerger Journal doesn't mean it's had a peaceful existence. It has even beaten the odds and weathered several crises before finding a new life on the internet.

This article is provided to you free of charge. If you want to support our team and promote quality journalism, subscribe now.

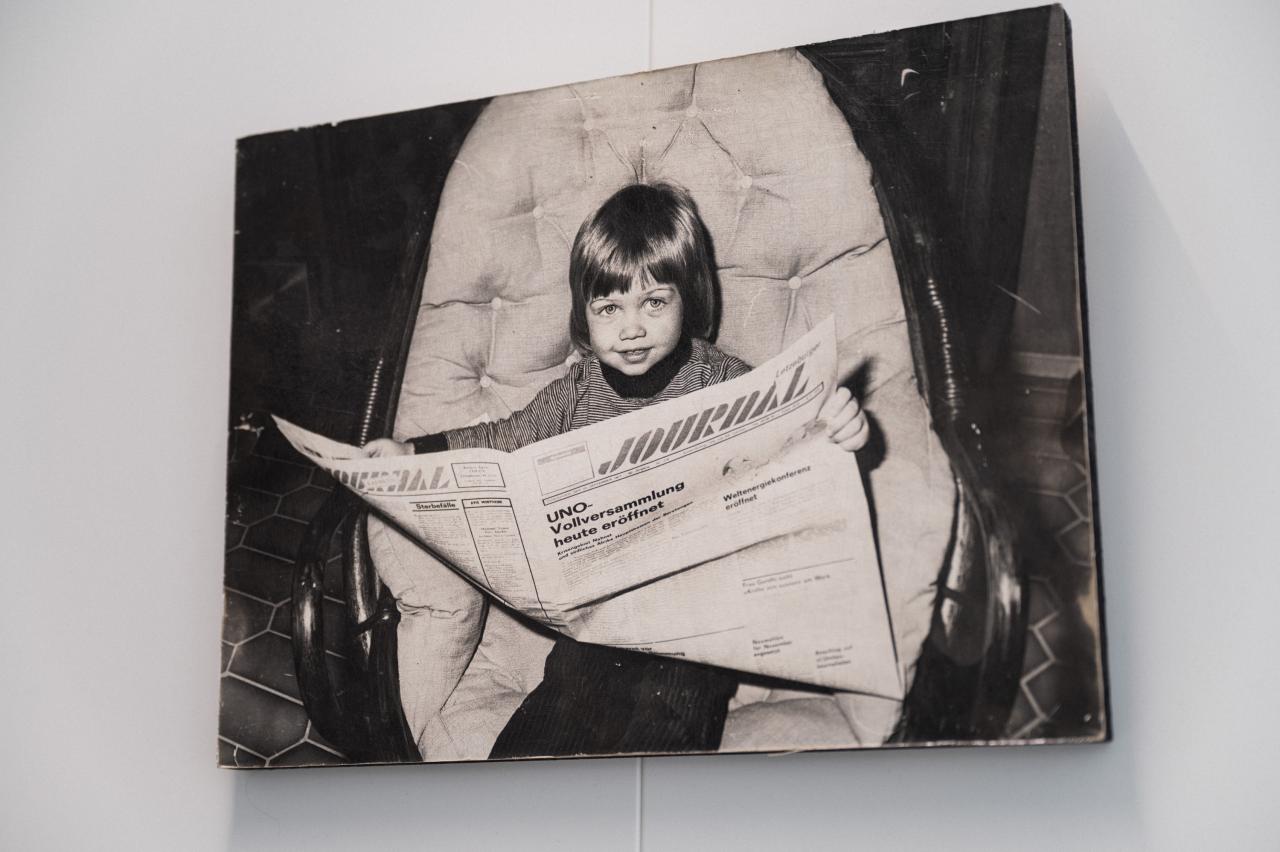

In 2023, the Lëtzebuerger Journal reaches the venerable age of 75. Admittedly, it still looks young compared to the two historic dailies that existed for a very long time before its birth: the Luxemburger Wort is 175 years old and the Tageblatt 110. But like them, it has lived through the major upheavals of the 20th century in the world and in the press, albeit with fewer resources. A former Journal journalist, Nic Dicken, expressed this very aptly in an article in the cultural magazine Ons Stad published in December 2014 – the edition was dedicated to the media -: "The journey of the Lëtzebuerger Journal since April 5, 1948 shows that you can keep a daily newspaper alive, constantly develop and reinvent it even without massive resources in money or personnel, but with a lot of commitment, involvement and heart." In fact, the Journal is the fruit of the marriage of reason of two dailies: Obermoselzeitung (Journal of the high moselle region) and Unio'n, brought together for the purpose of economic rationalization.

Two engaged couples from different backgrounds

-

The Obermoselzeitung, born in 1881 in Grevenmacher, "had liberal sympathies but was not the organ of the party", comments Romain Hilgert, former editor-in-chief of the Lëtzebuerger Land and author of the opus Les journaux au Luxembourg 1704-2004 for the Service information et presse du gouvernement. At the time, editorial offices and printing works were closely linked, and newspapers expressed the positions of those who printed them. Josef Essel, the Grevenmacher printer who took over the Obermoselzeitung, wanted to turn it into an independent, apolitical newspaper distributed on both sides of the Moselle. "The first issue of the Obermoselzeitung states: "The Obermoselzeitung cannot get involved in party and opinion battles, let alone settle frictions and disagreements, but will inform objectively and dispassionately, and avoid extremes."

The 1920s and 1930s were prosperous years for the daily, which had a circulation of around 17,000. It reported on viticulture, agriculture, industry and commerce – and politics once a week. Deemed too anti-Nazi by the occupying forces, the paper was banned in 1940 and its editor, Paul Faber, arrested. Publication resumed after a few days, fed by the Nazi propaganda service (Dienst aus Deutschland), but then stopped between 1942 and 1945 due to a lack of readers.

-

For its part, d'Unio'n was a pure product of the Luxembourg Resistance – being the organ ofUnio'n, the political organization created by a group of Resistance fighters who had seized a share of power at the Liberation and intended to continue playing a role after the government's return from exile. The paper focused on the themes that were in vogue at the end of the war: the reorganization of public life, the cultivation of language and the denunciation of collaborators. Its mottos: "Letzeburg de Letzeburger! (Luxembourg to Luxembourgers) and "Ech déngen der Hémecht!" (I serve the fatherland) attributed to Jean l'Aveugle.

The weekly, which became a daily under the name Tageszeitung der Resistenz - Volkszeitung für ein demokratisches Luxemburg (Resistance Daily – People's Newspaper for a Democratic Luxembourg), was even written in Luxembourgish in the early days, which made it difficult to write articles – news from abroad had to be translated – and also to compose them. German took over again in 1947. But above all, d'Unio'n needed a printing plant and a new lease of life. "After the first euphoric months of the Liberation, interest in Unio' n had evaporated," comments Hilgert. The liberal resistance fighters who had formed the Groupement patriotique et démocratique (the forerunner of the DP) – "a new party to make people forget that several members of the former liberal party had joined the sovereignist party close to the occupier", says Mr. Hilgert – wanted a more solid body to support and disseminate their ideas. At their head: Lucien Dury, resistance fighter, member of parliament and president of the Groupement, who will take over as editor-in-chief of the new daily.

The two newspapers found common interests – a printing plant of their own and the hope of adding their respective readership – and founded Imprimerie de l'Est in Grevenmacher. The Unio'n editors join the Obermoselzeitung, which the Lëtzebuerger Journal, whose numbering the Journal takes over. "For 67 years, the Obermoselzeitung came into people's homes, it was the friend of man and woman, son and daughter, " says the letter to readers on the Obermoselzeitung 's last day of publication on April 3, 1948. "It had something to say to everyone, each issue brought a multitude of entertaining topics, reported on what was happening in the big world and all the events in the little homeland. But there was one thing we hadn't yet found in our paper: articles whose content was coordinated with party politics. With the coming Monday, a change is taking place in this respect."

"[The Lëtzebuerger Journal] is a Luxembourg daily that wants to work for the good of all the children of this country, just as its two ancestors used to do."

Statement by the Lëtzebuerger Journal on its first publication

For its part, d'Unio'n reassures its readers: "We will continue to be the newspaper of all good Luxembourgers, especially those who, through their resistance, faithfully served the fatherland during the years of occupation."

The name Lëtzebuerger Journal is not chosen at random: it is the Luxembourgish translation of Luxemburger Zeitung, the great liberal daily that dominated the press between 1868 and 1941. "He was the spokesman for the steel industry, the country's major industry – and that's also a bit the reason for his decline, " explains Hilgert. "He was frowned upon in the 1930s because, as the steel industry did a lot of work with Germany, he supported trade policy with Nazi Germany." As a result, it didn't survive the Second World War and "it was impossible to recreate it after the liberation".

In its first edition, the Journal presented itself as "a Luxembourg daily newspaper that wants to work for the good of all the children of this country, just as its two ancestors used to do", with the motto "patrie et démocratie" ("fatherland and democracy").

The new press title received a cold reception from its competitors. "68 years and 5 years together make a day", ironizes the Tageblatt in a short piece wedged between social elections at the Ponts et Chaussées and unrest in Palestine. It further mocks the Journal 's mention to the DP: "Our affection to all those who want to run the affairs of state on a democratic basis." For the Tageblatt, these are "people with broad hearts, narrow horizons and short legs. He who embraces too much, embraces poorly." The Luxemburger Wort, born a century earlier and run by the archbishopric, commented: "The country's only independent newspaper is now tipping over into the political arena. (…) This is further proof that in a period as decisive as ours, it is not possible for any responsible individual or any newspaper to be politically neutral over the long term."

The voice of the Liberals

The young Journal already experienced financial difficulties during its first months of existence. In 1949, its offices in Luxembourg and Esch-sur-Alzette were closed. It asserted itself as the party organ, publishing the minutes of Groupement démocratique section meetings and party communiqués. In June 1948, for example, it was in the Journal that the DP fraction in the Chamber announced its resolution to support the enlargement of the government majority. And editor-in-chief Camille Linden, himself a DP member, published editorials criticizing the other parties and their newspapers. Thus, on the eve of the 1951 legislative elections, he wrote: "Luxembourgers have the choice between liberalism and socialism, which is a first step towards the reinstatement of slavery."

Passionate, "he was not to be disturbed under any circumstances", remembers former journalist Liliane Thorn-Petit in her account published on the occasion of the Journal 's 50th anniversary in 1998. And the DP's defense was expected of journalists in the political pages. "In the Chamber of Deputies, we had to note the speeches of the deputies, especially from the Liberal party of course, given that colleagues from the Social-Christian and Socialist parties ostentatiously dropped the pencil whenever it wasn't their deputies occupying the rostrum."

By the end of the 1950s, the Journal had 4,000 subscribers – not enough according to the DP, which was worried about the 1959 elections. The party organized the first relaunch of the daily and appointed former resistance fighter Henri Koch-Kent, who was not a member of the party, as its director. Although his aim was to broaden the Journal 's readership and thus the DP's audience, he failed to achieve this, no doubt due to a lack of resources.

The 1960s saw the resurgence of serious financial problems for the Lëtzebuerger Journal. Entrepreneur Jean Peusch took over the Faber family's shares and decided to have the Journal printed in Luxembourg. The publisher bought the site of a former garage on Rue Adolphe Fischer and set up the modern Imprimerie Centrale. The editorial staff also moved from Grevenmacher to Luxembourg. A double move that almost killed the Journal. "The Journal had the impression that Imprimerie Centrale was charging far too much for printing, " comments Hilgert. "This ruined the Journal." Not to mention the shares in the printing works that the Journal was supposed to recover, which mysteriously disappeared in subsequent balance sheets. And the readership didn't follow either, no longer identifying with a newspaper printed far from the Moselle.

"[After the Wolter case] a whole legal arsenal was directed against the Journal and against Rob Roemen in particular."

Claude Karger, former editor-in-chief of Journal

In February 1964, the Journal ceased publication. For 38 days, the journalists produced a ghost paper, continuing to write only to see their articles thrown in the garbage can every evening. But this existential crisis gave rise to a new awareness: not only did subscribers and DP members protest, but the Journal 's silence was noticed and deplored more widely in civil society. "This had unexpected consequences that we hadn't expected on this scale, " Lucien Dury wrote in the 1995 undergraduate thesis of a journalism student at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. "Suddenly, we realized that we couldn't simply do without the Journal." Journalist Jos Anen worked out an arrangement with the printer and came up with another source of income that would ease the Journal 's finances: company legal notices.

"This was a bit of a secret for the Journal: it had three or four pages of obscure company notices, " Hilgert chuckles. "In fact, the law requires that notices of companies' general meetings or their capital increases be published in several press organs. At one point, the Journal discovered that it could undercut the rates because its circulation was smaller. Companies would insert their ads with it because it was cheaper." It was a trick that gave the Journal "a new start", as it proclaimed when it returned to letterboxes on March 24, 1964 – enough to arouse the scepticism of Lëtzebuerger Land: "Le Journal has made its timid re-entry into the world of the Luxembourg press. Has it regained its strength and vigor, or is this only a temporary and artificial survival, the not-too-distant future will tell." The Journal is back on track, but it is above all the press subsidy introduced in 1976 by the DP-LSAP government to support competitors to the hegemonic Wort, and the increasing number of advertisements that will keep it afloat.

It was in the 1970s that the Journal's shareholder base shifted to the DP. Until then, it had been largely owned by the printers. The Peusch family's shares were sold to the non-profit organization Centre d'études Eugène Schaus, made up exclusively of DP members. The party thus had a firm grip on the management of the Journal, as well as the will to act under the presidency of Paul Beghin – which was not the case with his predecessor Gaston Thorn.

Always in search of a wider readership, the Journal 's management brought in a new editor-in-chief in the person of Jean Nicolas, who hired foreign correspondents – which not help the daily's finances – and tried to steer the Journal 's editorial line towards scoops and sensationalism (the ingredients of its later publication). He was dismissed after two years for launching a regional newspaper in parallel with his work at the Journal.

At the end of the 1970s, the Journal 's finances once again cast a shadow over its survival. Henri Grethen, appointed managing director of Editions Lëtzebuerger Journal, imposed strict financial management to prevent the ship from sinking. He also gave up the Monday edition, which is an important part of the Luxembourg media as it brings the weekend's news, particularly sports results. The reason: a change in the P&T schedule. This would force the printing works to work not on Monday morning but on Sunday evening, with overtime paid at double time for the workers. This is an extra cost that the Journal cannot afford – at the risk of losing even more readers and provoking a certain amount of mockery (Jean-Claude Juncker never shied away from mocking "the newspaper that doesn't appear on Mondays" during his weekly briefings).

Cultivating a difference

Despite these persistent financial difficulties, the 1980s saw a rebound for the Journal under the impetus of Rob Roemen, a journalist since 1975 and promoted to editor-in-chief in 1985. It was he who brought order to the daily's pages and introduced a more readable rubric. In 1983, the newspaper abandoned the numbering of the Obermoselzeitung and assumed its 1948 origins. For its 35th year of existence, it was distributed free of charge to thousands of letterboxes, so that as many people as possible could discover the fruits of its revival. For several months, 43,000 copies were printed once a week – a record print run for the modest daily.

"For years, the editorial staff and contributors had been striving to increase the quality of this newspaper, " says Rob Roemen in his editorial of November 8, 1983. "We believe we have succeeded better than we had hoped. The second step is to widen the circle of readers, a step which is now being introduced." The Lëtzebuergesetz then asserted its difference from other newspapers – particularly in terms of the subjects covered. "The Lëtzebuerger Journal is gradually becoming an indispensable newspaper for people who also want to be informed about those things that are taboo for others, " writes Mr. Roemen again in 1985, when the Luxemburger Wort was defending the very conservative vision of society of its shareholder, the archdiocese.

Romain Hilgert

Rob Roemen, a fervent defender and spearhead of the DP in his editorials, also published some thundering scoops: in 1984, he revealed the secret protocols of the coalition negotiations between the CSV and the LSAP. "Rob Roemen was surrounded by young, motivated journalists. The DP had just come out of government, and the Journal still had connections in the administrations, " comments Hilgert. "Sometimes information would cause the Journal to be consulted." This was also the time when Rob Roemen and his journalists were conducting their own investigation into the Bommeleëer. The Imprimerie Centrale received threats and asked them to drop their investigation. In 1990, the Journal again made headlines by publishing the testimony of the husband of a follower of the so-called Angel Albert sect, led by a doctor who recommended mixing blood and vegetables with meals. The doctor was disbarred by the Medical College. The case led to three lawsuits against journalist Roger Glaesener, only one of which he won.

During this period, the courts were examining the Journal's articles on more than one occasion. Legislation hardly protected journalists or their sources. The Journal was raided several times during the Wolter affair. Rob Roemen had learned of a tax penalty imposed on Michel Wolter, a CSV minister, in his capacity as president of the Bascharage tennis club. "The affair broke just before the elections, " recalls Claude Karger, journalist (1996–2000) and then editor-in-chief (2005–2020) of the Journal. "Subsequently a whole legal arsenal was directed against the Journal and against Rob Roemen in particular. Searches were carried out to find out who had passed on information to the Journal. The case was a landmark one, as it ended up before the European Court of Human Rights, and Luxembourg was condemned in 2003 for violating press freedom and the right of the press not to divulge the identity of its informants. This ruling led to a significant strengthening of the protection of whistleblowers."

"Le Journal was a bit of a school for journalists."

Romain Hilgert, former editor-in-chief of Lëtzebuerger Land

In the 1980s, the Journal aspired to be more than just a party organ. "A newspaper can't survive by being just a party press organ", says Rob Roemen, who breaks with a long-established tradition: when he writes about the DP, he no longer writes "we" but "the DP". At the same time, the DP revised its statutes: subscription to the Party Members' Journal was no longer compulsory, but recommended. However, the DP remains at the helm. "In 2008, Gusty Graas wrote about the Journal 's 60th anniversary ("Standbein der liberalen Presse: 60 Jahre Lëtzebuerger Journal – ein historischer Abriss", "A pillar of the liberal press: 60 years of Lëtzebuerger Journal – a historical overview"). Lucien Dury, Émile Hamilius, Gaston Thorn, Paul Beghin, Robert Wiget, Carlo Meintz, as well as Colette Flesch, Henri Grethen, Minister of Finance between 1999 and 2004, Norbert Becker, former top executive at Arthur Andersen and EY, Kik Schneider… have all been involved.

A closeness that has not always rhymed with affinity. "Political interest was always greater among opponents than among one's own supporters", writes Rob Roemen in his book Aus Liebe zur Freiheit – 150 Jahre Liberalismus in Luxemburg (For the Love of Freedom – 150 Years of Liberalism in Luxembourg). "Liberals treated – as the only political force – "their" daily lives always with neglect, a very rare and above all very incomprehensible phenomenon in politics." Romain Hilgert relates this cruel anecdote: "The DP very quickly began to despise the Journal because it didn't pull its weight. When he was Prime Minister, Gaston Thorn said to his secretary that she didn't need to put the Lëtzebuerger Journal on her desk."

As for the other media, they have always been somewhat condescending towards the Journal, "the newspaper that wants to be big", as Elisabeth Haas, a ULB journalism student who wrote her degree thesis on the Journal, described it. Nevertheless, the Journal was a good school for the journalists who worked there for varying lengths of time – putting out a daily newspaper with 8 or 9 people, each helping out and managing several pages, forges good professionals, whereas in larger editorial offices, young journalists are often given few responsibilities. "The Journal was something of a school for journalists, " confirms Mr Hilgert. "Many of them started out there and moved on to other titles fairly quickly. They went on to become journalists and even well-known politicians – and these people were a little ashamed to have started at the Democratic Party newspaper." For Mr. Karger, "there was also a big difference between salaries at the Journal and at the Wort, for example. In the Journal's history, many writers ended up at the Wort or the Tageblatt because they offered more."

This is how Robert Goebbels, later Minister of Economic Affairs, came to work for the Journal. He has an amused recollection of this, which he shared in the pages of the Journal 's 50th anniversary in 1998: "I wanted an internship at the Tageblatt, but there was no room. So I interned with Willy Muller and Guy Binsfeld. I was so enthusiastic that I kept making typos on the typewriter, and they had to come back after me to correct them. A week after I joined, Paul Elvinger complained to Jos Anen: 'What kind of Communist did you hire?' But whether at the Journal or the Tageblatt, I was never asked about my party affiliation. I know from experience that even the editorial staffs of political newspapers are often more independent than politicians of the same color like to be."

Other personalities to have passed through the Journal include Guy Binsfeld, founder of the publishing house of the same name, who experienced 38 days as a ghostwriter in 1964, as well as Willy Muller, Pol Wirtz, Lucien Thiel, later president of the Luxembourg Bankers' Association (ABBL), Michel Raus, a renowned cultural journalist who left for RTL Radio, more recently Arne Langner, who eventually left journalism for communications at ArcelorMittal and Annette Welsch, now at the Wort.

At the dawn of the Internet

For the Journal and its competitors, the 1990s marked the end of the hegemony of the printed press, even if few of them saw the digital revolution behind the so-called "new media", which would dry up their advertising revenues. Henri Grethen recruited a young Luxembourger who had just returned from Paris, where he had studied journalism, freelanced for Luxembourg dailies and worked mainly on the emergence of the Internet. He was none other than Claude Karger, who would succeed Rob Roemen almost ten years later. But the Journal didn't bet on the internet right away – lack of resources, obviously, but also ignorance of the role the internet was to play later on. "In the 2000s, a website was considered a nice-to-have by newspapers, they were promoting their articles published in paper format, " recalls Mr. Karger. "Everyone was starting to put their money where their mouth was on the Internet, without thinking about how much they'd make from it. It was only in the 2010s that awareness was raised and website-specific editorial departments were set up."

In 2001, the editorial office moved to the Imprimerie Centrale, on the corner of Rue Adolphe Fischer and Rue de Strasbourg, where it will remain until 2020. Until 2006, it will be sublet by the DP secretariat. That year, the Journal underwent a facelift, with a new layout and a new computerized page layout. The emphasis was placed on readability. A new distribution campaign was orchestrated to attract new readers: every two months, a copy was sent to 135,000 households nationwide.

Five years later, the Journal was forced by events to attempt a more profound relaunch. "The Imprimerie Centrale was only printing the Journal and the Land, which was no longer profitable, and they decided to abandon web printing, " recalls Mr. Hilgert. Faced with the realization that it would have to invest in a new press – not least to be able to offer color pages throughout the newspaper – the printing works preferred to throw in the towel. It was then that the Journal forged an industrial partnership with Editpress, publishers of Tageblatt and Le Quotidien. The two publishers shared the Sommet printing plant in Esch-sur-Alzette.

The Journal is taking advantage of this new departure to get a facelift. Gone is the blue color of the DP, and the Journal 's title now appears in black. Claude Karger states in black and white: the Journal is no longer a party organ. Even if it was a member of the DP, Marc Hansen, managing director of Éditions Lëtzebuerger Journal, who accompanied him to the press conference. "We had commissioned a series of market analyses and reoriented the Journal on that basis, " comments Mr. Karger. "There has been a certain evolution away from this idea that the Journal is the official organ of the DP. Other reflections came into play, such as languages or internet presence." In an interview in the now-defunct Le Jeudi, the editor-in-chief declares that he wants to "make an effort to reach out to young people and non-Luxembourgers". The new frontier for attracting a readership with little market presence.

"A newspaper cannot subsist by being only a party press organ."

Rob Roemen, Journal editor from 1986 to 2005

For Romain Hilgert, this detachment from the DP was a mistake. "It was a lie and a catastrophic failure. Le Journal no longer wanted to be the party newspaper because it wanted to find a clientele outside the party, which is understandable. But it was a fundamental mistake, especially as newspapers in the Grand Duchy are mainly sold by subscription. The average Luxembourg family subscribes to one newspaper, not two or three. For many, it was the Wort, or the Tageblatt in the south. The Journal was the second newspaper for liberal families. Once it was no longer the party organ, these families felt they no longer needed to support it."

For Claude Karger, however, the relaunch has paid off: "We've succeeded in our gamble by winning back new readers." Le Journal, which was again published on Mondays and increased its page count from 2005, saw its finances boosted by press aid. From 529,000 euros in 2011, it will receive over 974,000 euros in press subsidies in 2020. But the first projections of the press subsidy reform drawn up by the Gambia coalition darken the horizon: along with Le Quotidien, it is the only one to be penalized by the new mechanism which, to simplify matters, is no longer based on the number of lines but on the number of professional journalists. And in 2020 came the coup de grâce with the health crisis: "Everything was frozen for months: official announcements, advertisers' advertising budgets, even commune announcements, " recalls Mr. Karger. "Fortunately, the government paid out a special subsidy to the press."

Claude Karger

In June 2020, the directors of Lëtzebuerger Journal announce the end of the daily as a paper newspaper and the start of a new, exclusively digital existence. "It's been a long time since our newspaper launched a fundamental reflection on its future, " say Kik Schneider, Chairman of the Board of Editions Lëtzebuerger Journal, and Claude Karger. "This is taking place against a backdrop of changing readership habits, but also of changing corporate advertising strategies. Digital is playing an increasingly important role in these habits and strategies. At the same time, producing and distributing a daily paper is becoming increasingly expensive. The Covid-19 crisis has further underlined these underlying trends." This radical transformation is accompanied by a profound change in the editorial team itself, an episode that has been painful internally and criticised externally.

A new medium, a new editorial line: the Lëtzebuerger Journal that you've known for almost three years now has given itself the means to follow the same objective as its predecessors, by proposing subjects that its competitors don't tackle or hardly at all, documented articles, a journalism that moves away from the all-or-nothing and micro-events of hot news to explore the underlying trends and real issues of today's life, with a constructive outlook. Since 2020, mention of the Journal has disappeared from the DP's articles of association, and its directors, though mostly members of the DP, have no influence whatsoever on the work of the journalists.

What's most amusing is that this digital shift echoes an article in the 50th anniversary supplement, which tried to imagine the future and began as follows: "Tomorrow you won't be flipping through your Lëtzebuerger Journal" ("Morgen werden Sie Ihr Lëtzebuerger Journal nicht mehr durchblättern"). And indeed, you haven't been leafing through it, but scrolling through it on a screen, for the last three years.

Documentation

-

Les journaux au Luxembourg 1704-2004, Romain Hilgert, Service information et presse, 2004

bibnet-bnl.alma.exlibrisgroup.com -

Aus Liebe zur Freiheit - 150 Jahre Liberalismus in Luxemburg, Rob Roemen, 1995

www.a-z.lu -

"Le Lëtzebuerger Journal: un petit qui voudrait être grand", Elisabeth Haas, 1995

www.a-z.lu -

"Standbein der liberalen Presse: 60 Jahre Lëtzebuerger Journal - ein historischer Abriss" Gusty Graas, Lëtzebuerger Journal, February 2008

www.a-z.lu -

"Lëtzebuerger Journal : Freigeist und Pluralismus seit 1948", Nic. Dicken, Ons Stad, December 2014

www.a-z.lu -

"Un esprit libéral": le Lëtzebuerger Journal célèbre son 70e anniversaire", Jérôme Quiqueret, Le Jeudi, May 2018

www.a-z.lu