Listen to this article

For parents who are told at birth that their child's life expectancy is low due to a diagnosed disability, a world comes crashing down. The Lëtzebuerger Journal met two families who talk about their experiences and have never lost courage despite a difficult diagnosis.

The average life expectancy of a country can say a lot: medical progress, hygienic standards, environmental influences, social environment. Life expectancy can also be influenced by completely different factors including irregularities that occur at the birth of a child and indicate a disease or disability. Romain is one of them.

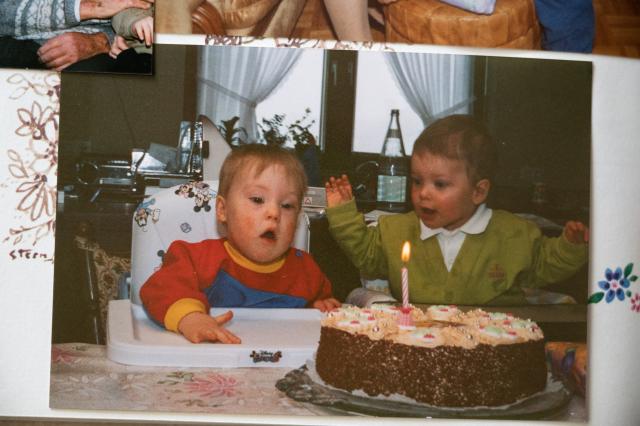

Romain was born on March 12, 1990. "There was never really anything that indicated a trisomy", Romain's mother says in retrospect. The docters had a suspicion at birth and they ordered analyses to be done. "We were told that we would know in three days." She describes these three days of uncertainty as a good thing – "the first contact could happen this way. The birth itself is stressful and exciting enough", the mother says.

Three days later, the phone rang. The doctor in charge didn't want to say anything on the phone. "Then you already know that the message will not be good. After that, there were many questions: "How do we organise ourselves? Can we even manage the situation as a couple?" The mother decides to not go back working and to be fully there for her son. "My husband had more difficulty accepting the new situation. The prognosis at the time for people with trisomy was very poor – I was worried." The parents had been told that Romain's life expectancy was lower and that he would have health problems – not more than that.

Romain

"Obesity could be a negative consequence. In addition, he would be less mobile and would have to undergo some surgical procedures." The latter had been the case, as she says. "We were told that we could get information. At the time we didn't have internet, so we reseached a lot in books. We found extremely bad things." There was a ray of hope during that initial period, she says. "We were told at the beginning that our son had a hole in his heart. All of a sudden we were told that this hole had closed itself."

Then the atmosphere in the delivery room changed abruptly

Annick is now 33 years old and was also born with trisomy 21. According to her mother Josiane, there was no suspicion of a disease at any time. "The atmosphere during birth was relaxed. As soon as she was born, that changed abruptly. I only got to see her for a moment and all of a sudden she was gone." After that, Josiane says, there was constant talk of further tests being done. "Suddenly there was a suspicion of jaundice, something that can happen more often with caesarean sections. That's why I couldn't have my child with me, as they told me back then." A nurse had taken great care of her daughter, yet the little one had been taken away again and again "for further tests".

A short time later, they both went home, then to the first check-up appointment with the paediatrician who was treating them. "She was upset and told us in a very harsh tone that she had to say something. She had good news and bad news. The good news was that Annick did not have a heart defect." Her husband asked for the bad news and the doctor replied: "Your child has trisomy 21." The doctor gave the parents a leaflet. "She didn't give us any additional information. But I still remember how she said that there was no special place to go for 'something like that'. Reassuring words did not come out of her mouth", Josiane remembers and shakes her head.

"The doctor was not sure at first and therefore did not inform us earlier. She justified herself by saying that it was her first trisomy case."

Josiane, Annick's mother

According to Dr Fernand Pauly, life expectancy in Luxembourg has made excellent progress in recent years. "I'll give you an example: when I was born, the average life expectancy was 65 years. In the meantime, life expectancy is around 80 years for a man who was born here in this country." So men got extra years without really having done anything for it, explains Dr Pauly. For women, the average life expectancy in Luxembourg is 84.6 years, according to Statec.

Due to Covid-19, life expectancy has decreased somewhat "because individual people have died earlier than expected", the doctor emphasises. At the same time, enormous progress has been made. "Life expectancy for cystic fibrosis (a congenital metabolic disease in which thick mucus forms in the cells and gradually clogs vital organs, ed.) has increased tremendously. We've had treatments for a good four years that are much more effective." This means that not only living conditions, predisposition and environment have an influence, medical progress also plays its part. Life expectancy for cystic fibrosis is now over 50 years.

Life expectancy, life perspective, quality of life

As much as this pleases the doctor, progress also brings a downside. "Parents would like to know what will become of their children in 30 or 40 years … but I don't know what progress medicine will make by then." Medicine knows a lot, he says, but just as much is still not clear. "This complexity of not knowing is difficult for people to grasp. It's understandable that they want to know everything, but unfortunately that's not always possible", Dr. Pauly points out. This speculation, as the doctor describes it, poses many questions for medical professionals. "What do I tell the parents if it is a trisomy, for example? Should the best possible or average outcome be described?" By this, the doctor means that Downs syndrome is more or less prevalent in some people than in others and cannot be generalised.

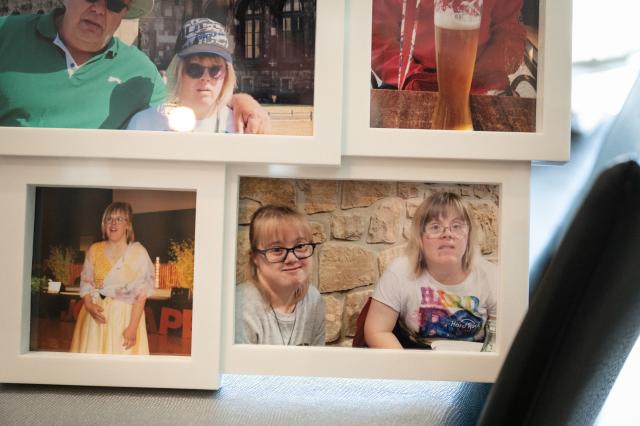

Annick

He gives a concrete example. "In the 18th week of pregnancy I see that the head looks a little smaller than usual. It may have developed well by the 22nd week. Do I have to report my observation immediately or should I wait? There is no universal answer to this." Tests are carried out after birth, including the so-called newborn screening. However, these tests are not compulsory. "In my eyes, we should have to screen the children for additional diseases (as the Lëtzebuerger Journal already reported, the screening is to be expanded, ed.). But how far can we go? If we do a lot of tests, we are committing ourselves as a society to look after and support these children later", adds Dr Pauly.

As a doctor, it is an extremely difficult situation, he says. "It is a state of uncertainty and dilemma: You are caught between the well-being of the foetus and the doctor's duty to inform. In addition, there is training for doctors, but it is not compulsory. For Dr Pauly, however, one thing is 100 per cent certain: It is important to provide perspectives and to tell parents what their child is capable of doing despite illness, instead of just talking about what is not possible. "No false hopes should be raised under any circumstances, but parents must be given something to hold on to." In addition, he says, it should be explained what is possible with medical progress. In conclusion, the paediatrician says: "When life expectancy is short, the days must be filled with life even more."

Josiane, Annick's mother

The parents felt left alone – "lost", reports Josiane, Annick's mother. "The doctor was not sure at first and therefore did not inform us earlier. She justified herself by saying that it was her first trisomy case." After another conversation with the gynaecologist – Josiane also describes this exchange as "completely off" – the parents went home. "We just cried." She depicts it as if they had been hit on the head. "We fell into a hole and it was hard for us to accept the whole thing – that's why we didn't tell anyone about it at first."

Lack of empathy from doctors

Josiane comes to her statement that the conversation with the gynaecologist also did not go as it should. "It was immediately after the appointment with the paediatrician. He asked how we were doing. Annick's father was beside himself." When asked why the parents didn't get this news until three weeks after the birth, the doctor replied, without batting an eyelid, "If you really take her home now, you don't have to worry at all. No matter whether it's school, education or leisure – such children are taken care of."

The mother and father did not immediately understand what the doctor was getting at, so the latter elaborated further: "You drop her off in the morning, go back to pick her up in the evening and you can do whatever you want all day. There are special schools and sheltered workshops. The child will get money, you will get money – what more do you want?" And that was still not enough, the doctor continued, "Don't worry about it, you don't have to keep her. I can call right away and someone will come and pick her up if you don't want to give your daughter away."

A statement that shocks, but is by no means an isolated case, as becomes clear in a conversation with Romain's mother. "The way we were told about our son's illness was not extremely negative, but we were told that we could give the child away."

Both women have worked all their lives for the well-being of their children, be it in associations, their commitment in the many discussions about admission to nursery schools and schools – according to Josiane, one nursery school teacher did not want to admit Annick, the other did everything to make admission possible – or in discussions with doctors so that Annick and Romain could be given a comprehensive check-up. "It's not easy to find doctors who are sensitive and don't give up on the children from the beginning. Our children deserve to have a future", Romain's mother stresses. "At three years old, he was like a child of 18 months. At that time we were worried about what it would be like when he was in his teens. We were afraid of the future."

In their private lives, too, both families met with a lot of incomprehension, with mothers who were friends and no longer wanted their children to play with them, and friends who turned away. "I could never understand such reactions. I find it hard to imagine that other kids would have experienced negative consequences if they had played with Romain", says his mother.

"It was as if Annick had a contagious disease", Josiane confirms. "I told a friend about the trisomy when she was visiting with her two children." The reaction of her friend shocks her to this day. "She started screaming, took her baby in her arms and said to her other child, 'You must not touch this child anymore!' That friendship ended right there. I threw her out the door." In contrast, she highlights the many great friendships that have been formed over the years. "We met a boy with trisomy in a playgroup. That friendship continues to this day." Annick grins from ear to ear. "He was my first boyfriend!"

"No false hopes should be raised under any circumstances, but parents must be given something to hold on to."

Dr Fernand Pauly, paediatrician

Annick and Romain are adults now and are partly independent. In addition to the Adapto transport service, both can rely on public transport to get from A to B – mostly to work. "Annick works, she plays basketball" – mother and daughter proudly display a photo with Prime Minister Xavier Bettel and his husband Gauthier Destenay at a sports tournament – "she is active in a drumming group and lives out her creative streak by painting." Annick manages a lot without her mother. "She also goes on holiday without me", Josiane says, laughing. She has always stood up for her daughter, as she points out herself. "I have stopped going to work and changed my wholel ife for her. It's exhausting, we've had to fight a lot and will have to continue to do so, but it's still a life worth living."

Romain loves to dance, especially Zumba. He has even worked with Luxembourgian dancer and choreographer Sylvia Camarda, he says with a smile. "I love being on stage." Like Annick, he also works in a retirement home and as Romain says, he is especially grateful that he was able to continue his work during the pandemic. "His leisure activities were more restricted, it was harder to explain why and how long it would last", adds his mother.

It is important to take time, she continues. "If there is any advice I can give other parents who are in the same situation as we are, it is to always stay positive – even if it is hard. As a parent, you can't say from the start that it won't work, you have to keep adapting." This adaptability and a great deal of flexibility are always top priority, she says. She is aware that this is not so easy to implement for everyone. "Nevertheless, the positive things should be emphasised. Often you have an idea (of how a life with a disabled child could be like, ed.) in your head that doesn't correspond to reality at all."

Related websites

-

Zesummen fir Inklusioun ASBL (in French or German)

zefi.lu -

Non-profit self-help organisation and independent representation of interests

trisomie21.lu -

Pedagogical and therapeutic support for toddlers and their family (in French)

www.elisabeth.lu -

Counselling and guidance with the help of the APEMH (in German or French)

www.apemh.lu