Wat mengs du? - Smartwatch: opportunity or danger for the healthcare system

Switch to German for original article

Listen to this article

What happens when prevention turns into panic? When millions of alarms go off, but hardly anyone knows what they mean?

In his Carte Blanche, Pierre Mangers writes about why smartwatches are not the problem – but rather their untapped potential – and why it takes reason to turn data into insight.

It starts small. One man. One watch. One alarm. That's all it takes to shake up a system.

Mr Schmit is 47, sporty. Slim. Healthy – that's how he PERCEIVES himself. His wrist vibrates for three days: "High blood pressure." Now he's at the GP. Between old magazines and new worries. Who should he believe – the watch or the medicine?

Two out of three alarms are correct. One is wrong. But that's not the point. The disturbing thing is not the error of the technology. It is the uncertainty of the person.

Technology with limits in a growth market

The Apple Watch has been measuring blood pressure since September 2025. A triumph of technology. A victory of data over the body. On paper.

The statistics are sobering. 41.2 per cent sensitivity, 92.3 per cent specificity. In plain language: less than half of the sick are recognised. Every thirteenth healthy person is worried.

Pierre Mangers

-

Pierre Mangers is a strategy consultant, chemical engineer, and statistician – he understands both structure and chance. After holding positions at ARBED, A.T. Kearney, PwC, and EY, where he was a Partner, he founded MANGHINI Consulting, a firm specialised in resilience, digital transformation, and strategic foresight.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, he was a member of the national Research Taskforce, contributing to statistical projections and economic impact assessments. He is the author of the study Economic Impact of the Services of the Agence eSanté and an active member of the Luxembourg Society of Statistics – convinced that numbers not only explain but also commit.

Samsung, Withings, Garmin – they all issue warnings. But they don't diagnose. A warning is not a judgement. Just a hint. At the same time, the market is growing. It pulsates faster than the wrists of its users. Smart rings. Wristbands. Sensors. Over twenty per cent growth per year. The body becomes a data source. The accessory becomes an instrument. And people – they become experiments.

Luxembourg as reflected in the figures

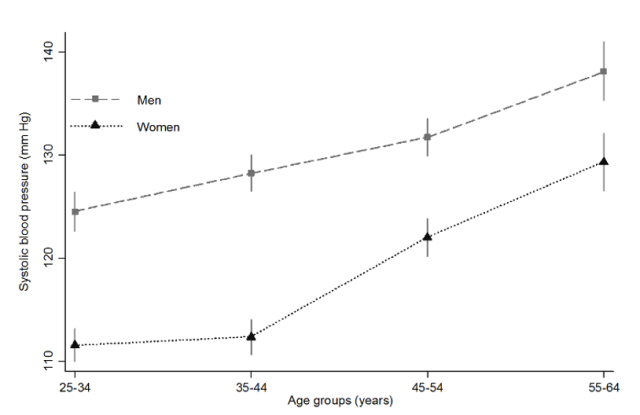

681.973 people currently live in Luxembourg. Around a third of the population suffers from high blood pressure. Around 60.000 of them could be wearing a smartwatch with a blood pressure alarm function by the end of 2025. However, high blood pressure depends on age, as the figure below illustrates.

Quelle: Individual risk factors and geographic variations, 2013 to 2015 European Health Examination Survey, 09/2016.

The EHES-LUX study showed ten years ago what remains: One in three people between 25 and 64 has high blood pressure. Up to seventy per cent are unaware of it or receive inadequate treatment.

This is not a special case in Luxembourg. It is the pattern in all affluent countries: hypertension – the silent national disease. High blood pressure is just one prime example of how data, AI and algorithms can gain insights from mere numbers. And there are many others.

This is where the role of smartwatches begins. Not a panacea, just a first, imperfect building block.

The paradox is as simple as it is ironic: the watch recognises the disease where it is worn least often. The majority of wearers are young, digital and healthy. Only some are over 45 – those for whom it counts. If you weight age and prevalence, you end up with 24 per cent: out of 60.000 users, around 14.400 are hypertensive. The watch detects 6.000, 8.400 remain undetected. 3.500 healthy people are falsely alerted, half of them run to the doctor. For the CNS, this means additional annual costs of 0.8 to 1.4 million euros. No drama, but a warning sign: when prevention becomes panic, the costs increase, not health.

Doctors in continuous operation

800 to 900 general practitioners are licensed, 200 to 300 work full-time in primary care. The additional 1.750 consultations per year are distributed among them. That's six to nine more patients per doctor per year. No reason for headlines, but noticeable – in a system that is running on reserve.

Europe is watching – Luxembourg could lead the way

Germany and France are waving goodbye. There, smartwatch data is considered a gimmick – a product of the lifestyle industry.

In the north, people are thinking ahead. Norway is introducing shared patient records with the Helse platform. In Sweden, patients have direct access to their data – wearables are part of this.

And Luxembourg? Everything is there: money, infrastructure, experience with the Dossier de Soins Partagé. The opportunity is not in the device. It lies in the system. Luxembourg is small enough to manage the risks. And big enough to be a model for Europe. Anyone who dares to integrate wearables and patient records will finally give shape to the prevention strategy promised in the coalition programme. In this way, the country could become what others lack: a laboratory and role model at the same time. A place where digital medicine is not only measured, but also understood. Those who integrate cleverly will benefit twice over – medically and economically. Because the market has long since outgrown the clock.

From technology to strategy

An alarm doesn't save anyone. It is not an emergency doctor, a medicine or a system. It is a signal – and like all signals, an alarm needs to be interpreted. Only when it is embedded in a functioning architecture can data be transformed into knowledge and knowledge into action. The device on the wrist is not the revolution, it is only its messenger.

It takes more than silicon and sensors to turn measurement into medicine. Incentives are needed to motivate patients to share their data and doctors to use it. We need education that de-dramatises false alarms before they destroy trust. And we require economic common sense, the realisation that prevention is always cheaper than repair. Recognising high blood pressure early not only saves heart attacks and strokes, but also money. Especially in a country where one in three people are affected, seventy per cent are unaware of it – and the CNS is struggling with a deficit of 25.8 million euros. Technology alone doesn't cure anything. But embedded in a system that can think, it could make the difference – between a smartwatch and an intelligent healthcare system.

"I wasted time, and now doth time waste me."

Shakespeare, Richard II

We have begun to count time – not to understand it. And perhaps that is the real loss. But isn't this exactly where the opportunity lies? If we no longer see time as an adversary but as a partner, digital prevention can become an instrument of progress – for patients, doctors and the healthcare system alike.

The technology is ready. Shouldn't we be, too?

Three scenarios and one decision

Luxembourg is faced with three options – and a test of its political intelligence. The first is the most comfortable: stand still. Leave everything as it is. The clock measures, the data dries up, the costs rise. The patient remains a test subject, the doctor a lightning rod, the system overwhelmed. The second way is called voluntariness – the favourite word of the half-hearted. Patients can, doctors can, nobody has to. A little data flows, a few euros are saved. But this is not the way to make history. That leaves the third way: not the easiest, but the one with the best prospects. A model in which devices are subsidised from a certain age and linked to the electronic patient file.

It costs money in the short term. In the long term, it can save money – infarctions, strokes, system costs – if it is cleverly introduced, data protection-proof and consistently evaluated. For the Ministry of Health, this is not an optional extra, but a duty. If you ignore technologies from the consumer world, you risk prevention degenerating into a fashionable phrase. We need rules that separate gadgets from medical devices and the courage to embark on a pilot project – from 2025 to 2030, scientifically supported by the LIH, flanked by incentives and evaluation. Only monitoring will show whether prevention not only prolongs lives, but also saves budgets. That would not be a coincidence, but a far-sighted policy.

Wat mengs du?

-

Once a month, we give space to a voice - someone who is an expert in a particular field. That expertise might come from academic study, professional experience, or personal insight: experts of everyday life, of an illness, of a unique situation - or simply of having a strong opinion.

Got something to say? Then send us your idea for an opinion piece to journal@journal.lu.

A look into the future

What began with a man and a watch has long since become more than just technology. It is a question of common sense – and politics. Does Luxembourg recognise the value of digital prevention – and is it seizing the moment to shape it?

You can dismiss it all. As a gimmick. As consumer electronics with a medical veneer. But in reality it is a touchstone. The watch measures, the person interprets. The system decides – or fails to decide. This is where the real opportunity lies: to understand technology not as a disruptive factor, but as part of a new order. If you are smart, you can link the data to the DSP and create trust, incentives and transparency. This is how digital innovation becomes a social strategy. Technology becomes responsibility. Data becomes meaning. Luxembourg could become what Europe lacks – fast, smart, bold: a laboratory of the future.

In the end, the equation is simple. Precaution is not a luxury. It is common sense. It saves suffering. It saves money. And it gives the system back what it needs most urgently: order within chaos.

-

Distribution of smartwatch users

- 25-34 years: 25.2 per cent

- 35-44 years: 30.0 per cent

- 45-64 years: 35.0 per cent

- 65+ years: 9.8 per cent

Prevalence of high blood pressure by age group

- 25-34 years: 10 per cent

- 35-44 years: 15 per cent

- 45-64 years: 30 per cent

- 65+ years: 66 per cent

From this: Prevalence (weighted) = 0.252⋅0.10 + 0.300⋅0.15 + 0.350⋅0.30 + 0.098⋅0.66

= 0.0252 + 0.0450 + 0.1050 + 0.06468 = 0.23988 ≈ 24 per centØ hypertension prevalence ≈ 24 per cent

Scenario Luxembourg

- 60.000 smartwatch wearers with blood pressure alarm function

- 14.400 hypertensive patients (24 per cent)

- Sensitivity 41.2 per cent → 0.41*14.400=5.904 undefined 6000 recognised (true positives: TP)

- Specificity 92.3 per cent → (1-0.923)*(1-0.24)*60.000 = 3.511.2 undefined 3.500 false alarms (False Positives: FP)

- Positive prediction probability 62.9 per cent (TP/(TP+FP), which means: of 100 alarms, around 63 are correct, while 37 are false alarms

Consequences

- In 50 per cent of the 3.500 false alarms, patients consult their GP.

≈ 1.750 consultations with a general practitioner - Around a third of the 1.750 consultations, around 585 cases, lead to a cardiological clarification

- In total, this results in additional expenditure of around 0.8-1.4 million euros per year for the CNS.

Key message

A modern smartwatch can detect almost half of hypertensive patients in Luxembourg (1/3 of the population), where 70 per cent were unaware or inadequately treated.