Luxembourgish craftsmanship - Claude Biever

Sponsored content Switch to French for original article

Listen to this article

Winter is coming... and Groupe Toitures et Cheminées, which brings together Sanichaufer Toitures and Cottyn-Kieffer, is making sure that Luxembourg spends it warm. Claude Biever, its manager, took over the company, created by his father in 1966, to turn it into a small empire. Today, he strives to build a "protective shield" around his business.

Foetz and the rest of Luxembourg are still sleeping. At Groupe Toitures et Cheminées, which includes Sanichaufer Toitures and Cottyn-Kieffer, the employees are gradually starting to light the wood-burning stoves in their showrooms. Outside, the sky is grey and the air is cool; a time to sit in front of the fire with a large, hot coffee.

Claude Biever, the group's managing director, is already in his office. From the workshops and storage rooms to the showrooms and sales rooms, the group's premises, although modest in size, seem enormous. With parquet floors, wooden doors and the smell of roaring fire, it's like being in a rustic chalet in the winter, ready to launch the next Christmas movie.

Half a floor down, a tall, bearded man who exudes an energy that would make you want to work on a Monday greets us: "Are you the boys who come for coffee?" Claude Biever has a big, infectious smile. "The group is there for people to understand that everything fits together", he says immediately. "But Sanichaufer Toitures and Cottyn-Kieffer are two separate companies." Without further ado, he invites us to visit his workshop; he and his company make one.

"Sanichaufer Toitures builds, repairs and maintains roofs", Claude explains on the way. "And once we are already on site, we can also offer other small jobs. Same for Cottyn-Kieffer, but for chimneys. Between them, the two companies offer "carpentry, roofing, waterproofing, tin smithing and maintenance" for the first and "chimney sweeping, flues, renovation by tubing, wood stoves and fireplaces" for the latter. We enter the workshop.

A large garage door leads to the outside. In front of it lies a panoply of parts ready to complete their chimney. This is one of the offers that make the company so successful. "The customer can come to us and say 'I need this part' and the workshop manager will draw it up with them. Two days later, it's ready and he can come and pick it up in front of the workshop." Like cookies coming out of the oven. The same applies to the site managers, for whom the missing part often represents a slowdown. "We have found our strength: we help out. We do what others don't want to do."

"We have found our strength: we help out."

Claude Biever

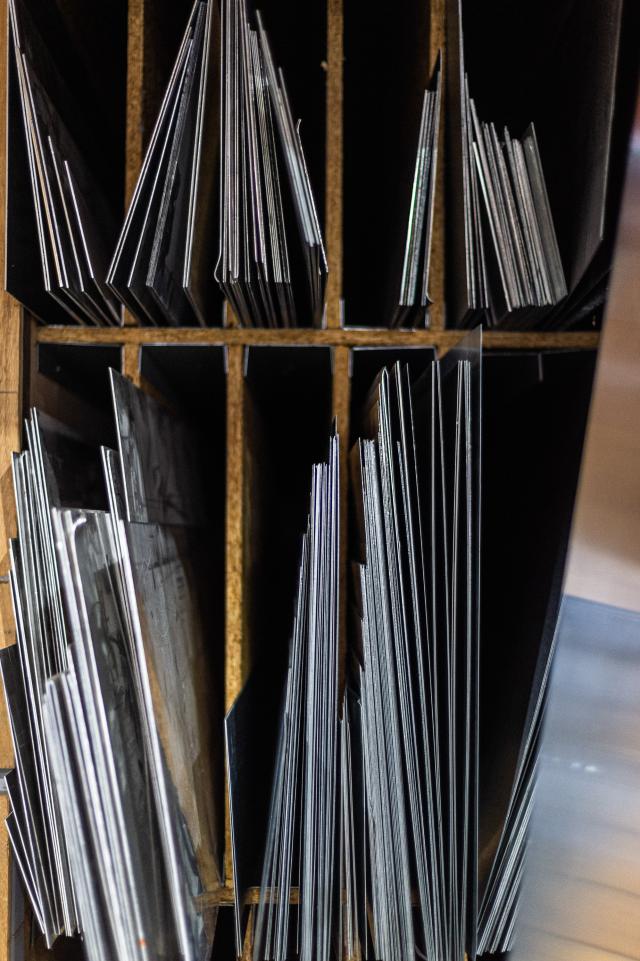

While Foetz is still sleeping, the workshop is working at full speed. "On the left is Sanichaufer Toitures. On the right, Cottyn-Kieffer", Claude explains. The whole place is covered in blue and orange. A Toyota forklift truck weaves in and out of the machines, one of which is a laser cutter that cuts rounds, squares and rectangles out of galvanised sheet metal. Everything runs like clockwork, the manager has left nothing to chance. This is the basis of his little empire.

An empire that has been built over more than 60 years, as Claude tells us as we go through each workstation. First stop, cutting. "My father, Jean Biever, set up on his own in 1959 and started the business in his own name. He started as a tinsmith and sanitary fitter. In 1966, he joined forces with a heating engineer and set up Sanichaufer to do sanitary, heating and tinsmithing."

Building an empire

At that time, the company was in Dudelange. It was to move to Foetz a few years later, but let's press pause for two minutes. Because before that, Claude was writing his own story, which begins at the Lycée Technique des Arts et Métiers (LAM): "When I was young, my father sent me to the craftsmen's school." He wanted to become a cook, but he didn't really have a choice. "I was told 'You have to do this because you are lucky that your father has a company and that you don't have to start from scratch.'" Cooking became a hobby.

A craftman's pride

Claude Biever on his passion for craftsmanship.

*in Luxembourgish

A forced choice which he is now very happy with: "Being a craftsman means having knowledge in many different trades. I am a mechanic as well as a tinsmith. I have been lucky enough to learn so many skills that have enabled me to progress in any situation and become independent." At LAM, Claude graduated from 11th grade and went straight into the family business. He has never known any other business, even if he would have liked to do some internships here and there had he had the time.

When he arrived at the company, everything fell into his lap at once. Second stop, folding. "My father died very early. So I had to learn everything very quickly" in order to take over. While his brother was running the business since, Claude was being trained by one of the company's technicians. "I did everything at the same time. My master's degree as a tinsmith, then a second one as a roofing and slating technician, and on the side, I learned to make estimates for construction sites." It was a busy period and "far from easy" for him.

After obtaining his master's degree, he finally joined forces with his brother in 1992. However, their partnership lasted only four years. There were no arguments on the horizon, but a professional conclusion: "When I arrived, I added slate roofing. My brother had already added the air conditioning. In short, Dudelange had become too small (to take on such a wide range of offerings) and our trades were no longer linked." So they split it up into "two separate independent companies."

Sanichaufer became Sanichaufer Toitures in 1994 and continued to occupy Dudelange until Claude found his "current premises in Foetz in 2001". Third stop, assembly. "Before the opportunity to take over Cottyn-Kieffer came around in 2003." At first, he integrated it into the company… "But it wasn't a good idea", he says. "So I turned Cottyn-Kieffer into a separate company again."

As our workshop tour comes to an end, it’s time for Claude to pose for a few photos. Portrait or landscape format? "I can lie down on one of the tables if you want to do one in landscape format", he laughs. "Otherwise, I make my best impression of a ship's captain! (laughs)" With both hands on a large lever resembling a sailboat bar – the reel unwinder – he is definitely not short of wacky ideas, which transmit good humour to a team facing the hardest day of the week.

"I have 85 employees", he says, as a few final photos of his are being snapped. "There are 15 teams, five of which only do repairs and small jobs on the Sanichaufer Toitures side, and four teams that do a dozen chimney sweeps a day, as well as seven teams of stove fitters on the Cottyn-Kieffer side. Finally, the icing on the cake, he added wood and pellet stoves to his offer in 2008 "at the request of customers". Today, Claude proudly offers the entire roofing cycle to his customers.

"Would you like some coffee?" The image of a good big coffee in front of a wood fire… We are (almost) there. Claude takes the corridor that leads to his office. In this area of the premises, everything is airier. The rooms are separated by glass. The manager calls this place the aquarium. As the coffees flow, he points to a frame. Pictures of an unusual building.

Passion for craftsmanship

This atypical building is the sports hall in Walferdange. It is probably his greatest professional pride, too. "An artistic and craft challenge", he says. "Because we worked with a product that didn't exist before. This was RHEINZINK's first corrugated zinc project, after a test phase. I had to draw up plans that were almost unprecedented." Few people thought he would succeed. In the end, his project won an award.

Proudest achievement

Claude Biever on the project he is most proud of.

*in Luxembourgish

"RHEINZINK put it in its 2000 calendar of the best building sites in the world. There were pictures from Miami, Moscow, Bucharest… and little Luxembourg!" These kinds of "personal challenges" are what the company is known for, and fortunately, because "it's far from being the most profitable". Close to the entire workforce is involved, so "if a site like this goes down, everything goes down". The Mamer high school was another one.

But whatsoever. Being able to be proud of what you have achieved is precisely one of the things that Claude is passionate about. It's also something he sees time and time again among his workers: "The boys arrive in the morning and create the pieces they'll be putting on the site later in the day. Then they photograph them and post them on Instagram to show how good they are. This satisfaction is very important, because a craftsman should be proud of his work."

"The love for one's work makes the value of the craftsman and, therefore, of his business."

Claude Biever

"For me, the passion was there from the start", he says. From his earliest childhood. "My first toy set was a bag of nails, a hammer and a wooden board. I had blue fingers from the start! (laughs)" As Claude grew up, he then turned to anything that could be taken apart and put back together. "It evolved like that. A craft is always a passion. Without passion, you can't be a craftsman. The love for one's work makes the value of the craftsman and, therefore, of his business."

It would be unthinkable for Claude Biever, who roofed his own house as a hobby, to give up this passion, even if "unfortunately I had to give it up too early". When you have to manage a company, working on the site becomes difficult. He is happy to put on his workman's helmet whenever he can to "pass on" his passion in his role as team leader, but his job now involves quite different issues.

Starting with his top priority: the human side. At the heart of his projects, Claude has always prioritised one thing: "The private customer is the most important." What he considers to be one of his most important tasks is to give special attention to every complaint: "Complaints for a company are very important." More than that, they are an opportunity. A customer who has a smoothly running construction site finds it normal. "But if something goes wrong and we solve the problem in the way the customer wants, we gain points. The likelihood of the customer recommending us to his friends is higher than for a normal customer."

When it comes to his employees, Claude knows he has a big responsibility. For him and for them. "Look at everything you read in the media", he laments. "Many people are already depressed before they even arrive at work. We have to be able to cheer them up. Everything in the company has to be rosy so that they can calm down. It's like someone going to boxing to let off steam."

From the company's point of view, keeping good workers is also important: "It's not just about money. It's also about comfort, benefits and the relationship you have with your employees." Succession is needed. "In December, one of our workers is retiring. He has been here for 42 years. Longer than me! (laughs)" For such cases, however, replacing the departing worker with a machine has now become a real option.

The challenges of an entrepreneur

Our cups empty, Claude heads for the showrooms. In the past, he has been President of the Confédération de la Toiture. He was also "very active as a member of the commission for the master's certificate examinations" of the Chambre des Métiers, which he would like to praise: "We got a lot of help from them." Training is clearly crucial for him and yet, it is "no longer worth the time and money invested"…

Training for nothing

Claude Biever on the time wasted training apprentices.

*in Luxembourgish

"In the craft industry, many craftsmen – myself included – are sad", he laments. "Sad because they train people only to lose them all. The state, which does not train, takes all our apprentices." Apprentices who are now only looking for an apprenticeship to obtain the CAP that will open the door to a big salary in a municipality. "It hurts constantly. It's sad that we have to depend on border workers."

His biggest sales room welcomes customers with a huge grey carpet bearing the "Fournisseur de la Cour" logo. Another source of pride, synonymous with quality. "The Grand Duke doesn't trust just anyone", says Claude. "In the past, there was only one Court Supplier per trade. This is no longer necessarily the case. Now it has several bakers for example… But one chimney sweep is enough!!! (laughs)"

"Craftsmanship is the pleasure of showing oneself and others what one is capable of."

Claude Biever

Another aspect of his job is to read a crystal ball: "The challenge as a business manager is always to know what is going to happen before the others. You have to orient yourself on the basis of what will happen in two- or three-years’ time. While Covid and the war in Ukraine have only had a "positive" impact on the construction sector, as people decided to invest in and optimise their homes, they have left it in a state of total limbo: "These are two situations that have destroyed our view of the future." It takes more than that to discourage the manager, though.

In recent years, Claude has made changes in the company that are now paying off: "We no longer heat with gas, but with wood. I put in solar panels to be independent of electricity. We are investing heavily in electric cars to get away from fuel. I make sure I have financial liquidity so that I am not dependent on the banks…" All this is done with one goal in mind: to limit the impact of the external environment on his company as much as possible. "I form a protective shield around the company", he summarises.

Despite these challenges, Claude remains convinced that becoming a craftsman is a good choice. "All handicrafts are worth their weight in gold", he says in his large car park, which is equipped with numerous charging stations. The Sanichaufer Toitures and Cottyn-Kieffer logos illuminate the slowly waking Foetz in orange.

"It's simple. If you have learned a trade, you have a job for life. Whether you are a baker, a butcher or a sheet metal worker. It's also a pleasure", he says. "Doing something with your hands – whether you are an artist or a craftsman – is a pleasure."

"The pleasure of showing oneself and others what one is capable of."