Steel, sweat and memories of the past: stories of a smelter

By Laura Tomassini, Lex Kleren Switch to German for original article

Léon Leszczynski is one of thousands of workers who used to be part of Luxembourg's iron and steel industry. Between lime works, dark tunnels and distant adventures in South America, he tells of an era that shaped the country - and of an everyday life that has long since disappeared.

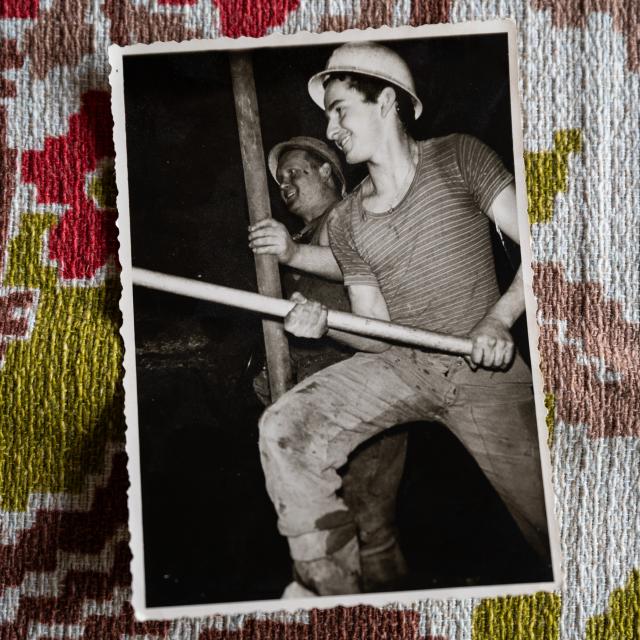

When Léon Leszczynski takes a seat in his living room and holds an old photo from Brazil in his hands, time seems to stand still for a moment. Not only the journalist and photographer listen to his stories, but also his daughter and goddaughter have gathered in Clemency to listen to the 92-year-old. Many of the terms used by the former smelter are no longer used today, but they bear witness to a time when Luxembourg achieved global stature with its iron and steel industry. The pensioner was also part of this history, which took him not only to the mines and steelworks of Minett, but also to South America.

But back to the beginning. At the age of 16, Leszczynski started working for Fischbach-Wiltgen, the Rumelange depot operator, cleaning soda and beer bottles. After a few months, the Rumelange native then went to work at the lime works of "Usines et Minières Berens", also in his home town. The job was actually only advertised for Luxembourgers, but a phone call and a good word from his previous employer enabled him to be employed there and gain his first experience in open-cast mining. "We sawed rocks, stones and limestone that weighed two to three tonnes each. The stonemasons then used them to make blocks, including for construction, " recalls Leszczynski.

From assistant surveyor to machinist

At the age of 17, he was employed at the "Montrouge Mine", a cross-border mine in Audin-le-Tiche ("Däitsch-Oth" in Luxembourgish), which was connected to the steelworks in Esch via an underground tunnel and where Leszczynski's father and two brothers were already working. The man from Rumelange spent a total of 13-and-a-half years here, first as an assistant surveyor and responsible for surveying the mine, then in the team of electricians who took care of the installation, maintenance and control of the machines, and finally as an "accrocheur", the person who attached the small mine cars to the so-called hoisting trains. "I was always told that I could become a machinist at some point, but nothing happened for a long time until I told our engineer Mr Dupont about it and he helped me to start my training, " recalls Leszczynski.

His new job: loading the wagons in the mines and using a so-called cable machine to take them out of the tunnel and bring empty ones back in. "It was very damp in the galleries and you had to be careful not to slip, because it was downhill and you would have fallen 400 or 500 metres without stopping, " says the former smelter worker. Other goods were also transported: the ore mixture to the "Chargeuse", the machine used to fill it into the blast furnaces; wooden support beams to the mines; or wagons to the transhipment point in Rumelange, from where the cargo was transported onwards, either directly to the blast furnaces in Belval or to the "Magasinnage", the storage depot near the Hiehl district of Esch.

You want more? Get access now.

-

One-year subscription€185.00/year

-

Monthly subscription€18.50/month

-

Zukunftsabo for subscribers under the age of 26€120.00/year

Already have an account?

Log in